|

This was an historic day on the Peninsula. Fifteen miles up the Aegean coast the first landing was being made at Suvla Bay. To divert the enemy's attention and to supplement the advance there and at Anzac, the 29th and 42nd Divisions attacked on our front that afternoon.

In spite of very terrible losses these two divisions gained some ground. The Turks, however, threw in reinforcements from their reserves concentrated at Maidos, a force with which they had boastfully threatened to drive us into the sea. The bulk of this army stemmed the advance at Suvla, but enough could also be spared for the fight at Cape Helles to annul our success. Indeed by August 7th only the forward portion of the Vineyard, between the Krithia and Achi Baba nullahs,

remained in the hands of the 42nd Division as the nett gain of the previous day's battle.

Our party of officers and N.C.O.'s spent the night at the Border Barricade sector. Up there on the left they had the pleasure of coming across our pre-war chaplain, the Rev. J.A. Cameron Reid, who was at that time attached to the 1st K.O.S.B. They got back to rest camp the following afternoon, having been compelled to lie low for a considerable time in the Gully, which had been heavily shelled by the enemy since sunrise.

The same day our move to the left sector was cancelled, and instead we were sent up at 8 p.m. to relieve the Chatham and Deal Battalion in the Eski line and to be in general reserve to the 42nd Division in the centre sector. On the trek forward two men of "A" Company (Captain D.E. Brand now in command) were wounded near Clapham Junction in the Krithia nullah.

By 11 o'clock "A" and "B" Companies were installed in the Eski line to the east of the nullah, with Battalion Headquarters on the inner flank, while "C" and "D" (now under Captain T.A. Fyfe and Captain R.H. Morrison respectively), with the Machine-Gun Section, occupied the line west of the small nullah. The trench between the two nullahs was in ruins owing to shell-fire directed against a battery behind it.

Indeed the whole position, though more than 1000 yards from the firing line, was a particularly unhealthy one with so much desultory fire going on in front. All the stray bullets seemed to drop in the vicinity and it was obvious that the Turk, taking advantage of the observation which his higher position yielded him, had in addition rifles or machine-guns trained on it. Occasional bullets, for instance, kept plugging into the ground beside Headquarters' dug-out. One of these

imbedded itself in a box which was being carried in by an orderly. After that anybody passing in or out moved, as the Colonel described it, with a well assumed air of having something to do in a hurry.

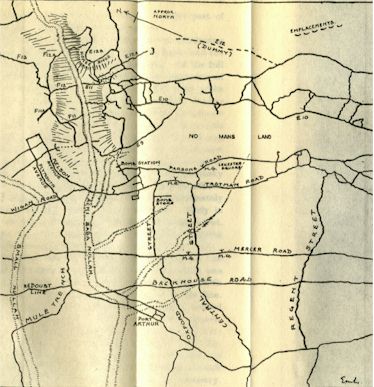

During our seven days here, the Battalion sent forward double parties of about three officers and 100 men each for night work in No-man's Land. They were extending No. 7 sap through the Vineyard, and digging across it a new trench, which was afterwards known to fame as Argyle Street.

It was at this time that the Colonel initiated a morning conference with company commanders, which met at Headquarters at 9 a.m. daily. It afforded an opportunity for an exchange of views upon the various questions affecting us and saved much correspondence, rendering the issue of formal Battalion Orders unnecessary except for special operations.

Preparatory to our taking over the trenches in front, Major Findlay, Captain Morrison, and Lieut. Leith spent the night of 11th/12th August in the Vineyard sector. About 7 p.m. on the 12th, however, the Turks started a determined attack on the Vineyard, and succeeded in recovering from the hardy Lancashire territorial most of the ground they had so gallantly captured on the 6th. During this action the Battalion "stood to," and "A" and "B" Companies moved forward to the

Redoubt line for eventualities. They returned the following morning, and in the course of the same day the Battalion took over the firing line to the right—that is from the small nullah to the Horse Shoe. On the left our front line (Argyle Street) was still far from safe and required further digging and sandbagging, while on the right the chief work in progress was a tunnel which was being driven from the Achi Baba nullah up to the Horse Shoe.

Before we moved up we had received three officers from the 2/5th H.L.I., Captain P. MacLellan Thomson and Sec.Lieuts. A. Barbé and Colvil. The former we lost at once to the 5th Argylls, who were short of Captains.

Captain A. Pirie Watson, R.A.M.C., took over the duties of medical officer from Lieut. Downes, who returned to his own unit, and for a time we lost the services of Major Neilson. He had been left behind ill in rest camp. Getting worse he was invalided home, but returned to us in record time.

On the night of 13th August, Sergt. D. Macdonald ("A" Company) who had served in the Battalion for thirteen or fourteen years, after previous service in the line battalions of the H.L.I., was killed in F12A while shifting a sand-bag on the parapet.

It was hard work getting our trenches into order and collecting the ammunition which was lying about in all sorts of odd corners; here a few unopened boxes, there a pile of loose rounds. The French on our right handed over to us 90,000 rounds of British ammunition, loose and in boxes, which they had retrieved in their sector. Besides ammunition, we made a big collection of miscellaneous equipment. Verey lights, bombs, etc., all of which were stacked centrally ready to be sent

down to Ordnance when opportunity might offer. Good progress was also made with the reconstruction of Argyle Street.

During the night of 15th August Lieut. Leith and Sergt. G. Downie crept out from our line near the small nullah and got close up to F12 at a point where a blasted tree with a shell-hole through its trunk stood out a few yards in front of the enemy's trench. They heard men conversing inside, and a shot or two was fired over the parapet. Grenades were also thrown from a work of some kind near the tree. These must have been on the off-chance of catching some of our people in the

open, for Lieut. Leith was confident that he and his companion were not spotted. Nothing was observed to indicate the presence of machine-guns in F12, but the ground in front of the trench was searched occasionally by enfilade fire from F13. The conclusion at which Lieut. Leith arrived was that the trench itself was but thinly held and that for its defense the enemy relied chiefly on fire from F13. After remaining in observation for a considerable time the scouts crept

carefully back, and the results of their work were passed to the Brigade at 5 a.m. with our morning progress report.

Later in the day we were asked to report to the Brigade in writing on the enemy's trenches in front of our sector, as to the feasibility of seizing F12. Our opinion was that there would be little difficulty in rushing F12 without incurring serious casualties, but that to consolidate and hold it under frontal and enfilade fire from F13 (in which the enemy appeared to have machine-guns) and possibly also enfilade fire from F12A, would be very costly. We suggested that before

any attempt on F12 should be made, at least the southern portion of F13 ought to be rendered untenable.

All forenoon rumors were floating about that arrangements were being made for an attempt to retake the Vineyard by troops on our left. Confirmation of these rumors came in the afternoon from the Brigade Major when he telephoned to inform us that the attack was to be delivered during the coming night, and asked us to send along, to assist, a catapult which was in use in our F13 bomb station, and the R.M.L.I. team, which had been left with us to work it. This was done, though

the special authority of the Naval Division had to be obtained before the corporal of the R.M.L.I. party could be prevailed upon to move his catapult and team from the spot where it had been posted by his own C.O. In view of the possibility that the enemy might be tempted, when he found the Vineyard attacked, to retaliate upon Argyle Street, fifty of "D" Company slept in F12, ready to move immediately to the assistance of the garrison of the new trench.

About 11 p.m. the Brigade gave us information as to the hour and other particulars of the attack, and instructions that we were to assist the attack by a heavy fire demonstration at 2.31 a.m. against the trenches on our front, and that if the C.O. considered the conditions justified it, we were to push forward and secure F12. The Brigadier agreed with our views put forward in our report, and impressed upon the C.O. that he did not expect him to attempt this unless an

unexpected favorable opportunity presented itself, but that in any case patrols might find out more about F12. Patrols were accordingly warned to be in readiness and, in the orders issued as to the fire demonstration, the firing line and support companies were warned that they might be required to advance.

Punctually at 2.31 a.m. on 16th August, we opened fire along our whole front. The intensity and volume of the enemy's reply were startling. Within a minute rifles and machine-guns were showering a hail of lead on our parapets. It almost looked as if they had been expecting an attack to develop from our sector. At any rate they had been very much on the alert and their trenches were strongly held. This strength they disclosed to an extent which at once proved the futility of

any attempt on our part to rush F12. It was not a case of a sudden burst of fire dying away rapidly. The General had instructed the C.O. to report to him by telephone at 2.50. At that hour there was not the slightest diminution apparent in the spray of bullets which was lashing our front. At least one machine-gun was pelting, at very close range, the barricade blocking the northern end of the stretch of F12 held by us—the very barricade behind which one of our patrols was

waiting to slip out into the open. Others were ripping up our sandbags here and there along the line. No patrol could possibly venture out into such a storm. This was reported to the General, who asked the C.O. to ring him up again when things became quieter.

Within about twenty minutes the machine-guns dropped out. The enemy had apparently come to the conclusion that any attack we might have been meditating had been nipped in the bud. Their rifle fire also slackened perceptibly, although it continued until daybreak much heavier than their usual night firing. On comparing notes, we found that two, if not three, machine-guns, had disclosed themselves in the dilapidated length of F12 between our barricade and the "shell-holed"

tree—a portion of the trench which we had hitherto regarded as entirely abandoned—and that there were more of them in the same trench between the tree and the small nullah; the exact positions could not however be located. Several had also been spotted in F13 and from the direction of F12A. The trap had been baited for us, and it was well that we had not walked into it.

At 3 a.m. the C.O. again reported to the General, who was much interested to hear of the nest of machine-guns we had discovered. He asked for a written report and sketch showing approximately their positions. He also informed me that the attack on the Vineyard had not been successful. Lieut. Leith took the sketch in hand at once and we were able to send it off, with the detailed report desired, before seven o'clock.

In Argyle Street about 10 a.m. Lieut. E.T. Townsend was wounded in the shoulder by a sniper's bullet.

The same day Colonel Morrison handed over the sector to the 7th H.L.I. and installed the battalion in reserve trenches immediately behind Wigan Road, Redoubt line and the First Australian line. Here we supplied various digging and salvage fatigues for four days. These were arranged in easy relief's so that we were able to wipe off arrears of sleep.

This was a difficult sector for the Quartermaster and his men. Setting out from rest camp each evening with the rations—and mails when there were any—loaded on mules, they ran the gauntlet across the open to a point where they entered the Mule trench, which ran up the side of the Achi Baba nullah.

This trench was not wide enough for pack-animals to pass in it. The traffic had therefore to be run to a timetable, one battalion's mules having to make the journey up to the advanced dump and away again before the mules of another battalion entered. Casualties on the way or delay caused by a recalcitrant mule were a constant nightmare, but Lieut. T. Clark always delivered the goods. From the advanced dump the rations were man-handled by companies to their own cook-houses.

Our water supply was carried in camel tanks, empty rum jars or petrol tins from Romano's Well. Later on water from even this source had to be chlorinated and the well lost its charm.

From now, about the end of August, till the end of October, life was somewhat monotonous, consisting of spells in the firing-line and moves to rest trenches, for short periods. While in the line we had little to do in the way of defending our trenches, as it was pretty obvious the Turk did not intend to attack. This did not, however, save us from providing large numbers of fatigue parties. The ground which we occupied soon became a network of trenches and we were always

endeavoring to push forward our front line by means of T-headed saps which were ultimately linked up. The object in this was to get as near to the enemy's front line as to allow our mining operations.

We found the Turk easily got the "wind up," more especially at night, and for very little reason he would start a burst of rapid fire, which sometimes would be kept up for a very considerable period. The staff frequently arranged various ruses to try and draw him in this way. For instance, in the end of August, on receiving news of Italy's declaration of war on Turkey, orders were sent to the front line that at a certain hour during the night, all troops would cheer, to give

the Turk the impression that we were going to attack. Of course this immediately started an outburst from the Turkish lines; rifles, machine-guns and a proportion of the Turkish artillery all joined in. To say the least of it, it was uncomfortable in the trenches, but few casualties occurred there. Most of the damage, which in reality was very small, took place well behind our lines, as the Turk on these occasions always fired high, and we came to the conclusion that they

must stand on the floor of the trench, with their rifles pointing upwards over the parapet, firing as hard as they could. It certainly had the advantage of disclosing Turkish machine-gun positions, and we were able, with the help of the artillery, if not to destroy the machine-gun, at least make it move to another part of the trench.

Battle of 12th July 1915

Again, on receiving news of a big advance in France, we carried out a similar plan to annoy the Turk. This time our artillery joined in, each battery firing a salute of twenty-one guns on selected objectives. This again very successfully drew the Turk, and probably he was never quite certain of our intentions, and may have formed the opinion that our infantry was unwilling to attack, an opinion which we formed of him later on with justification.

The ships which were lying off Cape Helles occasionally carried out minor bombardments. It was very interesting to watch the effect of their shells bursting when they got a direct hit on the Turkish lines, as of course we had no land guns of such heavy caliber. The ships were perfectly safe from any reply the Turkish artillery cared to make and we in the front line had to suffer for the navy's demonstration. No one really objected to this, although there was a lot of

"grousing," because we were glad to feel that we had the support of these big guns, which must have harassed the enemy tremendously.

The people that annoyed us most of all, however, were the trench mortar companies, who lived in comparative comfort in substantial dug-outs behind the front line. A detachment of these people would frequently visit our trenches, take up a position and proceed to bombard the enemy's line and bomb saps with doubtful success. It was enough, however, to annoy the Turk, and very soon spotting the position of the trench mortar, he would concentrate several guns on it, and at the

first sign of any enemy reply our trench mortar friends would pack up and make a hurried departure, realizing that they were due at another part of the line to carry out a similar demonstration.

The sickness which had started earlier on was continuing to take heavy toll of all the troops on the Peninsula and the battalion was gradually dwindling in strength. Of the full strength battalion which had landed at the beginning of July, there were only left sixteen officers and 498 other ranks at the end of September. While these numbers further decreased later on, Corps Headquarters realized the danger of this drain on the troops, especially as it seemed impossible to

obtain reinforcements from home, and started a rest camp at Imbros with the idea of giving a rest to officers and men who most required it. This camp was gradually moved to Mudros, and in all, three parties were sent, and the lucky ones benefited considerably from the change. Several officers joined us during this period; some of them unfortunately were not with us long owing to this sickness. Early in November we got our only fresh draft from home, Lieut. Andrews and

forty-two men from the 2/5th H.L.I. joining us. Major Neilson also rejoined the battalion at this time.

A few days after this the Battalion moved from the line for another short spell in rest camp to an area which was new to the Battalion, but had been vacated by the 155th Brigade before our arrival, they relieving us in the line. The officer's mess accommodation was somewhat limited and it was found necessary to form two battalion messes, Headquarters and half the officers occupying a fairly comfortable dug-out with matting roof for a shade. The other mess was constructed by

Captain Fyfe, who worried the Adjutant for working parties until he had dug a large enough hole in the ground as he considered would be necessary. The next problem was to get some sort of shelter, as the weather was beginning to break and we were endeavoring to prepare for rain. A large canvas sheet was produced in the usual skilful manner of Captain Fyfe for obtaining what he wanted, and then arose the question of how this roof was to be supported. Nothing daunted, he

approached the Colonel and managed to borrow some precious pieces of timber which had been used by the C.O. in his headquarters during the last spell in the line. This wood had been got with some difficulty from the engineers and was very precious. Once he had it in his possession, however, he seemed to forget the use it was really intended for, and finding that the beams were much too long to support the canvas roof, instead of considering some means of raising the roof or

lowering the beams into the ground, promptly sawed them in half and was perfectly satisfied with the result, which was really excellent as far as the other members of the mess were concerned. Very shortly after the mess had been finished, however, the C.O. came round to pay a visit, and was horrified, to say the least of it, to see the destruction that had been carried out on the borrowed beams. Captain Fyfe, however, had a ready answer and the trouble was smoothed over.

For some time past we had had signs that the hot weather was not going to continue and we had frequent showers of rain. One afternoon clouds began to gather from the south, and just as it was beginning to get dark we realized we were in for a pretty severe thunderstorm. With thunder we knew to expect rain and made hurried preparations, but no preparations we possibly could have made would have saved us from the deluge that came that evening. It rained steadily, in a way that

few of us had ever experienced before, for several hours, and dug-outs soon filled up with water. It was impossible to go to bed, and a weary miserable night was passed by everyone praying for the rain to go off. An unfortunate feature was that the Quartermaster the day before received from Ordnance the Battalion's winter clothing, and had issued it that morning. It had been issued by companies to the men in the afternoon and by night it was sodden with rain. It was

impossible to keep anything dry, and all we could hope for was some sunshine to follow after the storm. In the early morning the rain went off and when day broke there were some very funny sights. Few will forget the figure of Dow fishing in a deep pool of water for various articles of clothing with a stick, while his empty valise floated about on the surface. Fortunately the day was bright and warm and, as it is possible in a climate like that, we got blankets and clothing

dried.

To add to our other troubles an epidemic of jaundice had broken out about this time, which accounted for a great many officers and men leaving the Battalion. Aitken, if one could judge the severity of the attack by the color of the skin, must have been very ill indeed, because he was a deep yellow color from head to foot. He was determined not to leave the Battalion, and during his spell in the line before coming down to rest camp he had been regularly dosing himself with

various pills and only eating very light food, as far as it was possible to regulate one's diet. On reaching rest camp, however, he decided to adopt a kill or cure treatment and gave up taking the doctor's drugs. The mess stores consisted largely of cases of tinned crab and a good supply of whisky, neither of which, with the greatest stretch of imagination, could be called light diet. Aitken, however, took large quantities of both and returned to the line, white and feeling

very fit. It is difficult to make any medical man believe this story, but nevertheless it is true.

After this doubtful rest we received orders to return to the line and relieve the 156th Brigade, who a short time before had carried out a successful attack on a small sector of the Turkish line by blowing up their position and occupying the crater. It was this part of the line just east of Krithia nullah we had to take over. On arriving in the trenches about midday on the 21st November, and during the relief, we were somewhat disturbed by the enemy directing artillery fire

on the parapets and communication trenches, which, although some readers may consider strange, was quite an unusual occurrence. Little attention was paid to this, however, until about 4 p.m., when without any warning the enemy opened up a heavy bombardment on this particular part of the line which we held. This continued for about an hour and we were confident that the Turk was about to attack. Suddenly the artillery fire ceased and a red flag was seen being waved from the

enemy's trenches. Shortly afterwards two Turks came over the parapet but were immediately shot down. They were followed by an officer and a handful of men, possibly a dozen, who advanced a short distance, but when about half of their number fell, the remainder turned and bolted back to their trenches. All along the enemy's line we could see bayonets appearing above the parapet and there is no doubt that he intended to attack, but, apart from the few who actually left the

trenches, the attack did not develop. Our artillery during his bombardment, and more so after his artillery fire stopped, certainly directed a very heavy fire on his trenches, and we can only assume that the Turkish infantry was suffering from "cold feet" on account of this. Our casualties were practically negligible.

During the bombardment, an amusing incident took place with Buchanan's servant, Inglis, who was very deaf. This deafness increased with the climate of the Peninsula, but no one imagined that it had increased to such an extent as we found out that day. Inglis had gone to draw water at a neighboring well before the bombardment started, and later, when the Turkish artillery fire was about at its height, was discovered strolling along the support in the most unconcerned manner

with a bucket of water in his hand. Another of the servants, Kirk, who had been left at "B" Company Headquarters in one of the communication trenches, was found after the bombardment lying on the ground with a dud shell close to his feet. This shell, Kirk explained afterwards, had arrived a few minutes before, and striking the parapet of the communication trench some distance away, had ricocheted and landed with a thud and a cloud of dust beside him. He was still in the state

of being uncertain whether he was alive or not and was very glad, when spoken to, to find that he was able to reply.

A certain amount of repair had to be carried out on these trenches which had suffered from the bombardment and this kept us busy for the following days. After which we were relieved and moved back to reserve trenches. A message was received by the C.O. from the Corps Commander congratulating the Battalion on its steadiness during the "attack."

Life on the Peninsula was now becoming very uncomfortable owing to the weather conditions. We had many days of rain, and the Gallipoli soil is of a peculiar clay nature which sticks to one's boots when wet and is very difficult to remove. We had not even the luxury of roofed dug-outs in many places and had to do the best we could to shelter ourselves by means of our waterproof sheets.

The last few days of the month the weather changed again and we had several days very severe frost, which put us to our wit's end how to keep warm. Everyone wore as much clothing as they could possibly get on and some of us must have presented a very funny appearance. None will ever forget Major Findlay appearing at the C.O.'s Orderly Room with a Balaclava helmet on to keep him warm and a glengarry perched on the top of it with the intention of appearing properly dressed.

After this few days frost the weather broke again and on the evening of the 27th November we had a few hours' heavy rain which later on turned into driving snow. This was the tail-end of the blizzard which caused so much damage and loss of life at Suvla and finally decided the evacuation of that part of Gallipoli.

The Fifth Battalion, Highland Light Infantry

The Fifth Battalion, Highland Light Infantry in the War 1914-1918 |

|