|

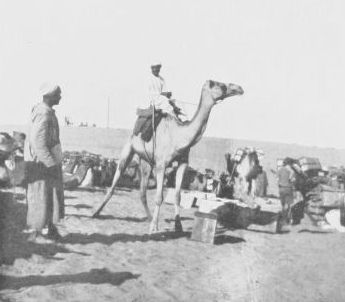

Water Camels, Mahamdiya

On this occasion the officer in command, having carefully laid out the loads at the prescribed distance and interval and quarreled with every specialist in the Battalion, went down to the camel lines, and loudly ejaculated the only Arabic word he knew—"Rice"—believed to mean headman. (The spelling of Arabic throughout these chapters is entirely phonetic.) A majestic figure in a blue dressing-gown rose and advanced beaming. There was a pause. All the camels were required. "Alle

Gamell," observed the officer hopefully. It is said that every Arabic word means some form of camel and it seemed possible that Gamell was an Arabic word. The difficulty lay rather in the "all"! Rice broke into a flood of Arabic—but gave no orders. The officer repeated his phrase, trying the conversational, wheedling, and minatory tones in turn—but it was useless. He therefore held up eighteen fingers—not of course simultaneously—eighteen being the number of camels required

for one of his precious lines of loads. This was more effective. Rice fell upon his myrmidons, beat up a number of drivers, who beat up eighteen camels. The loading party assisted to beat, and so amid threatening and slaughter the first line was roughly filled, most of the camels lying down facing the wrong way, which necessitated much abuse and whirling round of the forefinger before they were shipshape. Rice, now satisfied that all was well, was horrified to perceive

nineteen more fingers displayed before his nose, and the officer, seeing that time was getting short and the present method would take an hour at least, directed his men to go straight to the point, and to attack the camels themselves. There resulted an appalling pandemonium, everyone beating everything and the camels snarling like a pack of wolves; and at length the drivers, seeing that the white men meant business, sadly abandoned their leisure occupation of parasite

hunting and rushed upon them. After receiving some of the blows intended for their charges, they managed to get most of the camels disentangled and the difficult business of loading began. The officer, however, realized that the natives had no idea that we were leaving Katia for good, and being a kind-hearted man, did not wish them to lose their few belongings. He therefore summoned Rice again, and said slowly, "Mahamdiya—Katia never no more"—accompanying the words with a

gesture of violent negation. Suddenly the awful truth broke on Rice, and he set up a long and despairing howl, on which all the drivers left their charges, ran screaming to their household goods and began hastily to pack them into their bosoms. Immediately half the camels lurched to their feet with horrid sounds, began to turn round like teetotums and went a-visiting among their friends. The Mark VII. Camels, as if by instinct, sought the Mark VI. (We should perhaps remark

that this refers not to a difference in the brand of camel, but to the fact that the Battalion used Mark VI. ammunition for the long rifles, with which they were still armed and Mark VII. for the Lewis guns and great care had always to be exercised to keep the two separate.) The camel with the bombs scraped off his load against the camel with the fuel. Order became chaos. The exhausted but undaunted fatigue were about to dive into the welter, when the officer observed the

approach of the O.C. camel escort with his men in all their war-paint, ready for the march. Silencing his scruples he hastily called off his own party and, reporting to the unsuspecting new comer that all was in order, he fled to the trees, where they were just in time to throw on their equipment and get into position before the column started. It need hardly be said that they felt as if they had done a hard day's work, and were already the victims of an excellent thirst

before the march began.

The Battalion moved straight back to Mahamdiya, starting at 2 p.m. and arriving at 7.15 p.m. The men were very tired, but only two fell out during the march and the contrast with some other marches strengthened our belief that, given a good meal before starting, proper halts every hour, and above all, marching not in the breathless humid hours of the morning but in the drier afternoon, after the breeze had sprung up, we could cover considerable distances without loss.

We found our old camp standing, and the men gladly renewed acquaintance with the few little comforts they had left behind in their packs, while the officers reveled in regained valises and there was much very necessary bathing. "C" Company went out to No. 11 Redoubt, far the best of the line, as it was right on the sea and just in front of some old ruins which yielded a number of interesting things in the way of coins, lamps, pottery and the like. We never could find out who

had lived there, but there must have been a town of some importance to judge by the size and solidity of some of the foundations. Probably it was a Greek or Greco-Roman Colony. A week later the post was taken over by two platoons of men who were unfit for heavy marching and who formed part of a newly constituted Brigade Details Company, a formation which gave us a chance of sparing many who were physically unable to stand the heavy strain of infantry work in the desert.

We remained at Mahamdiya till August 26th, occupying the inner picket line at night, and training by day. On that date the Brigade moved to er Rabah, a large palm grove, a mile or so north of Katia, which it closely resembled. After réveillé at 3.45 a.m., and breakfast at 4.30, the Battalion moved off at six, reaching er Rabah at 11, but not being able to move into its bivouac area till 1 p.m., after which camels had to be unloaded, fires lit and dixies boiled before tea

could be served to the men. The march was extremely trying, the nights at this season being very wet, and the hours before midday a torment of damp heat. Several men collapsed as they marched, suffering from a kind of heat-stroke. It was in this march that an unnamed hero "was three times sick in the presence of the G.O.C."—an act of courage immortalized in a Brigade order, of which the writer still possesses a treasured copy.

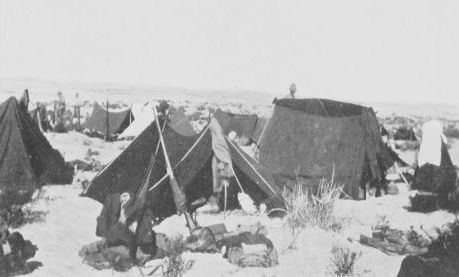

At Rabah we occupied an area some little way from the trees, but we came out provided with one blanket per man and sticks with which we could rig up bivouacs. Two poles were stuck up in the sand with a guy rope attached to a peg to keep each in position. They stood a blanket length apart and two blankets were tied to the top of them by their corners, the other corners being pegged down to the ground, thus forming a shelter open at each end, and capable of holding two or three

men and their not very numerous belongings. A little study enabled the architects to combine the maximum of shade with the maximum of wind ventilation. Save for a short period at Romani and then at el Arish, when the tents were brought up, these makeshift shelters were our homes until proper bivouac sheets and poles were issued in June 1917. They had to come down every night when the blanket was required for covering, and so we slept beneath the stars. This form of habitation

led to a tremendous demand for bits of string—especially for little bits which attached the blankets to the poles or to the pegs. It was so easy, when dismantling a bivouac at night, to lay a bit of string on the ground, where it was swiftly and inevitably covered with sand and lost for ever. In consequence the careless or stringless took to sticking the peg through a hole in the blanket and then to making a hole to stick the peg through and "this thing became a sin in

Israel."

Sheikh's Tomb, Katia

Some distance outside the camp we dug a series of little trenches for pickets which were occupied at night by companies in rotation. Stand-to for everyone was at 3.45 and was often prolonged by mist. But our only enemies were usually ineffective bombing planes and exceedingly effective swarms of flies and also little whirlwinds which rushed across the camp amid howls of execration and collapsing bivouacs. There were many chameleons about and they were in that state of

disordered fancy which is supposed to attack the young man in the spring. We would capture them and, after emblazoning our names and numbers in indelible pencil on their flanks, an indignity which completely ruined their carefully worked out camouflage schemes, would set them to fight, which they did with extreme ferocity and remarkably little effect, nature having provided them with no weapon of offence whatever. The contest was chiefly one of swelling up and making faces,

and was extremely exhilarating to the onlookers. Our only other diversion was the not always popular one of battalion exercises in various stages of the attack. Few attacks, alas, ever planned out exactly like that when there was a real enemy, but the exercises kept us fit and thirsty.

Our stay at Rabah lasted until September 11th, when we marched due west and took over a camp from the 4th R.S.F. north of Romani and close to the great landmark Katib Gannit. This was a vast pile of sand, its top 240 feet above sea level and rising a good 150 feet at a wonderfully steep angle from the minor sand dunes around it. It was visible for many miles to eastward, and had been used as an observation post in August and consequently heavily shelled. Our camp was in among

the sand hills, which are unrelieved by scrub and of an almost incredible yellowness. "B" Company took over Redoubt No. 2, one of the chain with which we had already become familiar at the northern extremity. The rest of the Battalion were employed in training and route marching, while ranges were established for rifle and Lewis guns. Parties of officers and men were now allowed to go to Port Said for three days' leave, a privilege of which we were glad to avail ourselves.

Port Said has few attractions, but hard roads and iced drinks are a great lure after months in the desert. The journeys to and fro were naturally not devoid of incident. The leave parties marched up to Mahamdiya in the early morning, over some miles of bad going, and Headquarters are to be congratulated on the fact that no party of ours at any rate ever left on an empty stomach. At Mahamdiya they reported to the R.T.O., a versatile officer of the 5th, whose administrative

career was almost cut short by an untoward incident about this time. A great one, owning a private trolley for railway "scooting," 'phoned the R.T.O. office, Mahamdiya, to enquire whether the line from that place to Romani was clear. He received an answer in the affirmative and set off gaily. At about the same moment a large ration train left Romani for Mahamdiya. They met about half-way, and the engine driver, whose career had not taught him a proper reverence for red tabs,

blew his whistle and carried on. The superhuman agility of the trolley's crew just succeeded in getting their vehicle off the line before the train reached it, but the R.T.O.'s office at Mahamdiya stank in official nostrils for many days.

The line to Port Said, however, was a metre gauge one, laid down on the beach which runs as a narrow strip between the sea and the lagoons. The aforesaid R.T.O., sitting equably among a cloud of flies, would inform you on arrival (1) that the train which should have been the 8.30 from Mahamdiya had only just left Port Said, and could not arrive here for three hours, (2) that it had not run at all the day before, owing to engine trouble, and (3) that the sea washed away parts

of the line most days. He would then propose a second breakfast. About 12 the train would arrive and the party be packed like herrings in the narrow trucks. At 1.30 the one person who really ran the line—the engine driver—would have finished his lunch, and would proceed to refresh his iron steed by the simple expedient of pouring in water from a canvas bucket. Now comes the great moment—will she start or won't she? There is a puffing, a snorting, a few wild jerks, and then

amid a tremendous scene of enthusiasm the 8.30 moves slowly off.

"Six an hour from 'ome an' duty![1]

Keep it up till we arrive."

And we would go

"Bumping round the Bay of Tina

Cocked up on a truss of hay."

[1] Songs on Service.—Crawsley Williams.

But the author of this poem was a gunner—the infantry did without the hay. On the right lies the deep blue of the Mediterranean, its waves often washing the track. On the left the light blue of the lakes stretched away till it mingled with the blue of the sky, and no man could say where water ended and sky began. Occasionally there would be islets, dark blots apparently hanging in the air, or a flock of far-off marsh birds, with legs amazingly lengthened and distorted by the

mirage. Port Said would be reached about 3.30—and then the Canal had to be crossed. The return journey would probably be worse. One returning party paraded in good time for the 5 a.m. at Port Said. They left at midday, but on reaching the only siding on the line, about half-way to their destination, they found the up-train stranded with the engine broken down. Their engine therefore deserted them and hauled the derelict train into Port Said where the drinks are. They

themselves reached camp between eight and nine at night. So the journey cut rather badly into the three days' leave. Officers who were free to do so would return by the Egyptian State Railway west of the Canal, as far as Kantara, and then go up by the desert line to Romani, perched on a truck of tibbin—a bumpy and smutty ride. It was no uncommon thing, especially at night, for the trains to break in two, as the suddenly varying gradients among the sand hills put a tremendous

strain on the couplings, and one would be left stranded in the desert until the forward half reached a station, where some one might notice that it seemed unusually short. Those who only knew the line when officers could sleep in a cushioned sleeping car, and be whirled from the Gaza railhead at Deir el Belah to Kantara in eight or ten hours, have no idea what the line was capable of in its palmy days, when passenger traffic was not its forte—of the hopeless efforts to find

out where any train or any truck was going to, and when it would go there; the long halts and sudden unheralded departures, at the moment when the passengers had at last dared to get out to stretch their legs; the rending struggles to board mountainous trucks piled high with rations; the starving quest for biscuits in forgotten canteens at stations where no one ever lived. Let us try and remember these things when next we are abusing the obscurities of Bradshaw or find our

train five minutes late.

About this time our Brigade commander, Brigadier General Casson, who had been with us since the early days in Gallipoli, left us, to our great regret. He was succeeded by Brigadier General Hamilton Moore.

Bivouacs, El Rabah

The Fifth Battalion, Highland Light Infantry

The Fifth Battalion, Highland Light Infantry in the War 1914-1918 |

|